Charge of the Electron

The purpose of this experiment is to measure the smallest unit into which electric charge can be divided, that is, the charge of an electron \(e\). The method is the one proposed by R.A. Millikan in 1910 1. A small sphere of mass \(m\) having a charge \(q\) can be suspended in air by applying an electric field of field strength \(E\) to balance the gravitational force on it.

We then have $$ mg = qE $$

We neglect here the (very) small buoyant force 1 . The charge \(q\) will in general not be the electron charge but rather an integral multiple of it:

$$ q = ne $$ with \(n = 1, 2, 3, … \)

When the measurement is repeated several times, e can be found as the largest common denominator of the measured charges \(q\).

In the absence of an electric field, the electrons will reach a constant terminal velocity \(v_T\) after a short time. The viscous force balances the gravitational force, so that the net force acting on the droplet is zero and we have:

$$ mg = Kv_{T} $$

where according to Stoke's law: 2 $$ K = 6\pi\eta r $$with \(\eta\), the viscosity of air \(\eta=1.831×10^{-5} Nsm^{-2}\) at \(18^{\circ}\)C. From measuring the terminal velocity \(v_{T}\) of free fall, the mass of the spheres can be determined. Then, Equation 1 can be used to find the \( q\) on each sphere.

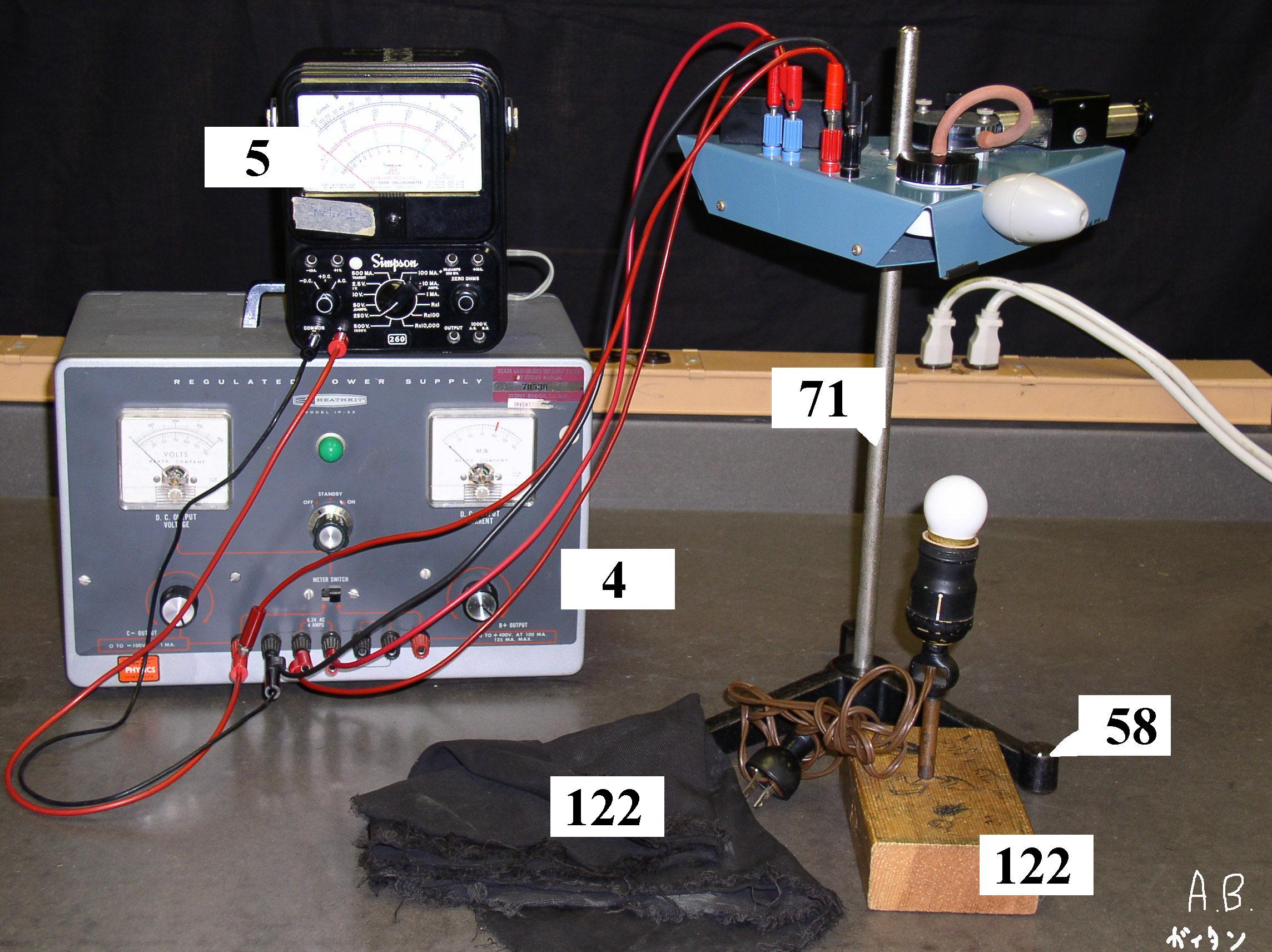

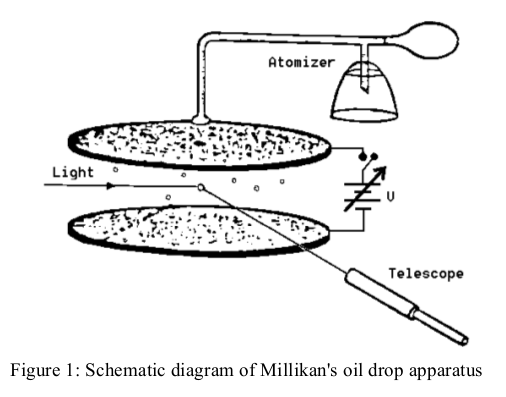

Figure 1 shows a schematic sketch of the experimental set-up. A closed chamber is placed between two capacitor plates 0.4 cm apart, in which a uniform electric field \(E\) can be built up (remember, \(E = V/d\).

The chamber is illuminated by a small lamp. Charged spheres (a suspension of latex in water and alcohol) can be blown into the chamber through a tube and a nozzle, and be viewed there through a telescope with a calibrated scale (spacing of graduations 0.5 mm). Note that the telescope gives an inverted image. In our apparatus, \(r\), the radius of the spheres \(\approx0.50\mu m\).

- Turn on the light and focus the telescope on the end of the nozzle which is used to blow spheres into the chamber. Then pull the nozzle back out of the field of view. Spheres can now be blown into the chamber by squeezing the rubber bulb.

- Blow some spheres into the chamber and watch them (they will look tiny). They will quickly reach terminal velocity \(v_{T}\) and should all fall at the same rate in the absence of an electric field. Measure this velocity by timing the travel of particles over a known distance with a stop watch. Repeat several times until you get a set of consistent values. Calculate the mass from the average terminal velocity. Compare to the value you obtain by calculating the mass using a density of \(1.05 \frac{gm}{cm^3}\) (error estimate!).

- Blow more spheres into the chamber and watch them falling. Now turn up the electric field. You will see them reverse direction and reach a new terminal velocity which now depends on their charge \(q\). Since you want to measure the smallest charges, select one that is least affected by the \(E\) field (i.e. one that is stationary at high fields) and adjust the voltage V to hold it stationary. Write down the value of \(V\) (hence \(E\)), and repeat the measurement 20 or more times trying to find spheres with slightly different charges.

- Calculate for each measurement \(q\), and determine from these values the charge unit \(e\) as the largest unit of charge consistent with your data. This is best done by guessing n for each measurement (you should observe groupings in the distribution of the measured charges \(q\) and assign an integer n to every grouping) and plotting your measured values \(q\)(n)versus n. The measurements should fall on a straight line with slope \(e\). Compare with the literature value of \(1.602×10^{-19}\mathrm{C}\), and discuss possible deviations.

The equipment we have doesn't always work very well. Therefore rather

than follow the above procedure we propose you observe the phenomena

using the actual setup and then take your data using a simulation:

oPhysics Millikan Oil Drop Simulation

The simulation is very similar to the real experiment. Rather than producing many drops simultaneously you can focus on one drop at a time. To produce a drop, click the button labelled “Create New Particle”. The terminal velocity can be determined with the Voltage equal to zero. The large divisions on the scale on the screen are cm (ie. the plates are about 5.0 cm apart). The stopping potential can be found by adjusting the using the virtual “Voltage”. Once you have determined \(v_T\) and stopping \(V\) for one droplet, simply summon a new one and repeat until you have enough values (often 10-12 is fine).

In your analysis, use the expression for mass of the droplet given in the oPhysics simulation: $$ m = k (v_T)^2 $$ with \( k = 4.086*10^{-17} kgs^2/m^2 \) 3 .

Click here for details of the analysis

These notes are for the oPhysics Millikan Oil Drop Simulation. The simulation has an introduction/manual that should be sufficient to perform the experiment. It is recommended to do a few practice runs to get familiar with it.

For 10-12 "particles" (oil drops) list the following in a table/spreadsheet:

- The terminal velocity with no electric field;

- The mass calculated from the velocity with the approximation given;

- The voltage required to keep each drop stationary (zero velocity);

- The corresponding electric field (calculated);

- The corresponding charge (calculated).

Make a list of all charges in ascending order, then deduce the unit charge from the list. Consult your Teaching Assistant: this table/spreadsheet may be sufficient to complete the assignment in Brightspace.

Hovering over these bubbles will make a footnote pop up. Gray footnotes are citations and links to outside references.

Blue footnotes are discussions of general physics material that would break up the flow of explanation to include directly. These can be important subtleties, advanced material, historical asides, hints for questions, etc.

Yellow footnotes are details about experimental procedure or analysis. These can be reminders about how to use equipment, explanations of how to get good results, troubleshooting tips, or clarifications on details of frequent confusion.

Considering buoyancy of the droplet in air, the "apparent weight" would be $$ w = \frac{4\pi}{3}r^3(\rho_{oil} - \rho_{air})g $$

Stoke's Law applies for spherical droplets in a medium with small buoyant force and low Reynold's number.

This expression is not standard but is applied correctly in the simulation. It treats the droplet radius as a known quantity and folds that value into the \(k\) value.

Chapter references are for "Modern Physics for Scientists and Engineers, 4th Edition" by Stephen Thornton and Andrew Rex, Cengage Publishing. Section 3.2